Why Doing Big Stuff Can be Good Politics

The conventional wisdom that bold action equals political doom isn’t as clear cut as some want you to believe.

One of the most challenging aspects of political analysis is the problem of small sample size. There have only been 46 presidents in the nearly two and half centuries of American independence. Every circumstance is different; times change. Political coalitions shift. Therefore, it is very challenging to use history to predict the future. But political punditry demands predictions and hates humility, so Twitter, Cable television, and political podcasts are filled with cocksure predictions about what will happen based on a handful of imperfect precedents. Over time, these predictions calcify into conventional wisdom. A recent tweet from Jake Sherman of Punch Bowl News embodied a particularly persistent piece of conventional wisdom. In a longer, well-reported thread about the political and legislative backdrop for President Biden’s American Jobs Plan, Sherman offered the following take:

I don’t want to pick on Jake, an excellent reporter, but the gist of his tweet — and much of the punditry around the Biden agenda — is that doing big, bold things is bad for one’s political health. This is such an accepted piece of political wisdom that is rarely questioned, but is it accurate? Are Joe Biden and the Democrats playing with fire by pushing big, progressive initiatives like the American Rescue Plan and the American Jobs Plan?

I don’t think polling or history supports that contention. In fact, doing more, not less, might be the better strategy to maintain the majority.

First Term + Stuff = Loss

The conventional wisdom that doing stuff is bad is based on two circumstances. First, the two years after entering office are when presidents succeed legislatively because it is when they have the most political capital. Additionally, each of the last five presidents entered office with their party in control of Congress as well. Second, presidents traditionally take a drubbing in their first midterm.

In 1982, Ronald Reagan’s party lost the national popular vote by a whopping 12 points.

In George H.W. Bush’s first midterm, the Democrats expanded on their House and Senate majorities.

Bill Clinton’s first midterm saw the Democrats lose the House majority for the first time in four decades.

Democrats lost a record 63 seats during the 2010 midterm while Obama was President.

In 2018, under Donald Trump, Republicans lost 40-odd seats in the House and lost the House popular vote by more than seven points.

George W. Bush is the only modern exception to this trend. During the 2002 election, Bush’s approval rating was artificially inflated by a “rally around the flag” movement, which we now consider a historically disastrous response to the 9/11 attacks. Bush took his shellacking in 2006 when the Republicans lost the majority in the House and the Senate.

Whether Biden and the Democrats pass everything on their agenda or nothing, the Democratic majorities are at risk. Partisan redistricting alone could give the Republicans the House majority. In the Senate, Democrats must hold onto seats in Arizona and Georgia — two states Biden won by the narrowest of margins but have recently passed new laws to make it harder for Black and Latino voters to participate.

Based on this, it’s easy to see why most people assume that doing big stuff leads to big political defeats. But I think the reality is more complicated than this oversimplistic historical rendering suggests.

What Causes Backlash

History is very clear that first-term Presidents almost always face a backlash in the first midterm. Eric Patashskin is a Brown University political science professor that studies political backlash. He recently spoke to Vox’s Andrew Prokop about avoiding the seemingly inevitable reaction to a newly elected President.

According to Patashnik, there are several features that appear to make certain policies more likely to produce backlash, including:

When they impose near-term visible costs (such as tax increases)

When they threaten the social identities of groups (say, religious beliefs, or challenges to the status of groups like police officers)

When they generate resentment about the provision of benefits to “undeserving” groups (for instance, conservative backlash to welfare or benefits for undocumented immigrants)

When they challenge the power of groups that are highly dependent on or attached to existing arrangements (this applies to a myriad of special interests)

When policies don’t represent the views of average voters (such as George W. Bush’s Social Security privatization effort, and House Democrats’ push for the cap-and-trade bill rather than staying focused on recovery from the Great Recession)

Patashnik’s research explains some of the political fallout from Bill Clinton’s Crime Bill, Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act, and Donald Trump’s tax boondoggle. I have no doubt elements of these bills helped juice turnout amongst the opposition. But politics is much more complex than blaming one particular bill for an electoral landslide.

Let’s take the Affordable Care Act, for example. In the Obama White House, we entered the political minefield of health care with eyes open to the political risk. As Obama wrote in his memoir

“What Axe is trying to say, Mr. President,”Rahm interrupted, his face screwed up in a frown, “is that this can blow up in our faces.” Rahm went on to remind us that he’d had a front-row seat at the last push for universal healthcare, when Hillary Clinton’s legislative proposal crashed and burned, creating a backlash that contributedto Democrats losing control of the House in the 1994 midterms. “Republicans will say healthcare is a big new liberal spending binge, and that it’s a distraction from solving the economic crisis.” “Unless I’m missing something,” I said, “we’re doing everything we can do on the economy.” “I know that, Mr. President. But the American people don’t know that.” “So what are we saying here?” I asked. “That despite having the biggest Democratic majorities in decades, despite the promises we made during the campaign, we shouldn’t try to get healthcare done?”

The concept of health reform was kinda, sorta popular when we started, and it became less popular as it moved through the sausage factory. Obama took it on, not because he thought it would help us win the 2010 midterms, but because it was a once-in-several generations opportunity to do something really important that had eluded presidents for nearly a century. While the repercussions of the 2010 election have echoed for more than a decade, trying to provide health care to millions of Americans was the right decision.

For all of the political risks of the ACA, it’s not the only reason, or even the primary reason, Democrats lost in 2010. And if you don’t believe me, just ask the more than a dozen House Democrats that voted against the ACA and still lost their seat that fall. A House Democrat in a tough district that opposed the ACA fared about as poorly as those that enthusiastically embraced the law.

The other interesting part of the Obama anecdote is that Clinton’s political troubles in 1994 are not attributed to the law he passed (the Crime Bill) but the health care law he failed to pass. If one president suffered for passing a law and the other suffered for not passing a similar law, it suggests that the connection between big-ticket items and electoral doom is perhaps more correlation than causation.

One could argue that the problem in 2010 was not the less popular bills passed by the Democrats but the very popular bills the Democrats failed to pass. After health care, the appetite for political risk-taking had diminished in the Senate to the point that they failed to act on some bills that would have improved the economy and the political environment, including legislation to rein in dark money, strengthen unions, and close tax loopholes for companies that shipped jobs overseas. There were other efforts to pass bills that would have juiced the economy and put more people back to work quicker that never left the gate because they faced certain doom in the Senate.

An Outdated Model?

These “backlash” analyses are about trying to understand what one side does that sparks higher turnout on the other side. But perhaps this is an outdated way of looking at politics.

This view assumes that everyone is making judgments about what is happening in Washington based on the same set of facts. Unfortunately for democracy, we haven’t been in that situation in a long time. Fox News and the rest of the information arsonists in the Right-Wing media ecosystem have sufficient reach and insufficient shame to push entirely false narratives to drive turnout among their base. It worked in 2016, 2018, 2020 and could very well work in 2022.

Look at the example of the role "Defunding the Police” played in 2020. Joe Biden and nearly every Democrat on the ballot opposed the concept of "Defunding the Police.” Yet, Republicans and the Right-Wing media were still able to use the issue to drive turnout through false attacks and misleading media narratives.

Therein lies the problem. What Joe Biden and the Democrats actually do is secondary to what the Right-Wing media wants to tell their voters that Joe Biden and the Democrats did.

Some have argued that the Republican penchant for lying creates a permission structure for Democrats to be as bold as they would like. For example, if the Republicans are going to call every health care plan — no matter how moderate — Medicare for All, why not just support Medicare for All? As tempting as this concept may be, it ignores the importance of the counterpunch. The Republican “Defund the Police” smear would have been much more effective if Biden and the Democrats had not been able to credibly respond with evidence of their opposition.

While the GOP’s “alternative facts” don’t give Democrats carte blanche to channel our inner Chomsky, it does reveal the limits of trying to reverse-engineer our strategy based on what fires up the Republican base. Bear with me for a second because this is a crazy idea:

Instead of spending all of our time worrying about what not to do, what if we spent our time looking for broadly popular things that also fired up our base?

And that’s exactly what the American Jobs Plan does.

Not All Big Ticket Items are the Same

Ultimately, this is a purely theoretical argument. It’s impossible to prove the counterfactual or offer a simple explanation for an event as complex as an election. The historical examples tell us very little about what will happen. We can only look at the data before us and make an educated guess about the best way forward. Even if you accept the conventional wisdom that doing big things lead to political doom, there is a lot of evidence that suggests that Biden’s American Jobs Plan is the exception that proves the rule.

Every piece of legislation has two parts: what it does and how it’s paid for. The American Jobs Plan is unique in the sense that both parts are supported by huge bipartisan majorities.

According to a recent poll from Invest in America and Data for Progress, nearly three in four voters, including a majority of Republicans, support the American Jobs Plan. Each of the key provisions of the plan has greater than 60 percent support.

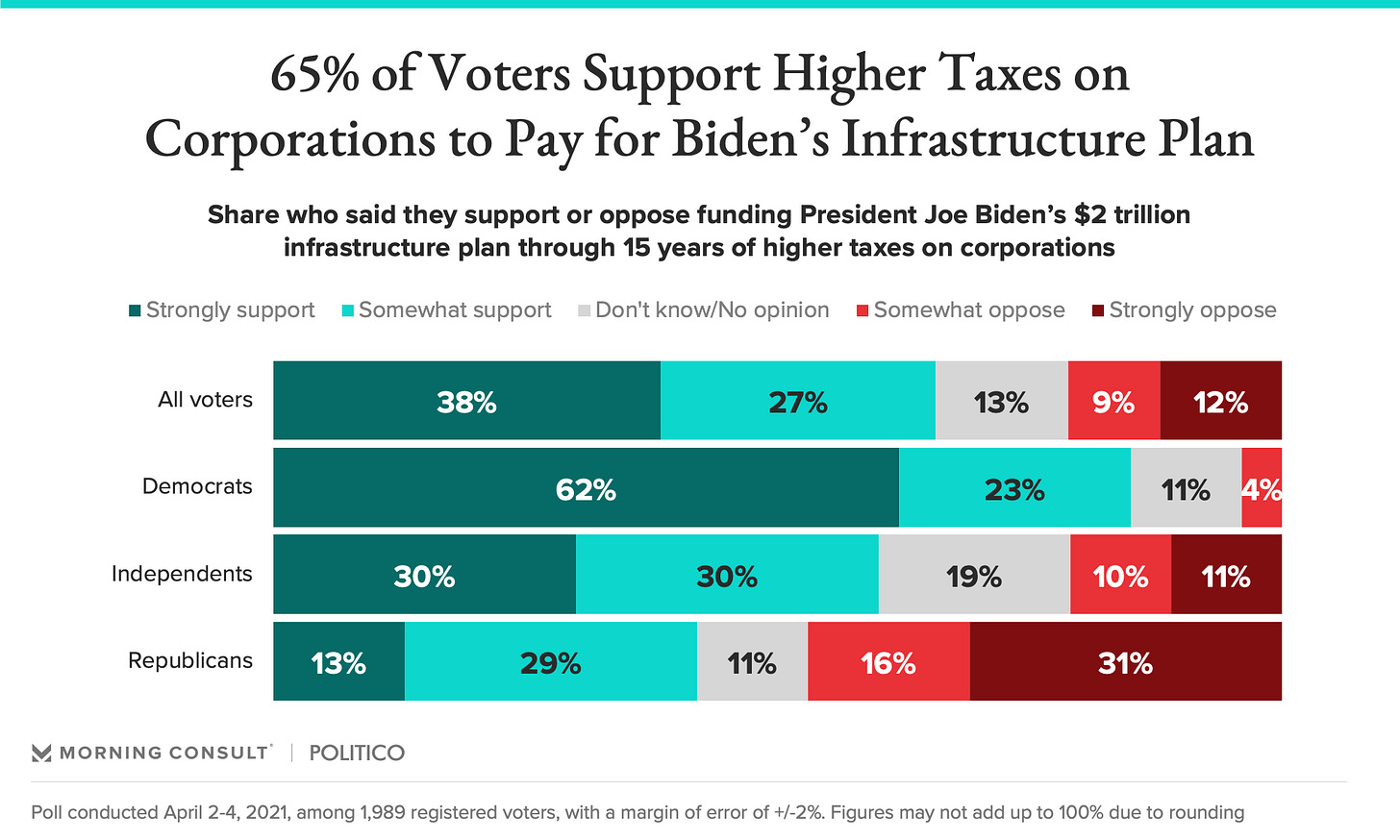

Because of the broad popularity of the core provisions of the plan, the GOP has promised to attack the plan because it’s paid for by tax increases. There are two problems with this approach. First, relying on tax attacks is more muscle memory than political strategy. Republicans have been running against tax increases since Ronald Reagan. It may have worked then, but it hasn’t worked since. Second, not all tax increases are created equal. Biden’s plan is funded in part by raising taxes on corporations. A Politico/Morning Consult poll found that 65 percent of voters support higher taxes on corporations to fund infrastructure improvements. Even four in ten Republicans support raising corporate taxes to pay for infrastructure.

There is a lot of road to travel between now and the hypothetical day when Joe Biden signs a version of his jobs plan, but it’s hard to imagine a better starting point or a better argument against the idea that doing big, popular things is bad politics.

Sometimes the political conversation becomes so warped with data, history, and spin that common sense is completely lost. In this case, imagine telling yourself that the Democrats would be better off in 2022 if they did NOT pass a bill supported by three-quarters of Americans. Yet, that’s the exact position being argued by a few strategists, some moderates, and a lot of media types.

For Biden and the Democrats trying to hold onto dangerously narrow margins, the question isn’t whether to do more or less; it’s whether to do popular things that people want and make sure the public knows you did them. If that is the case, passing Biden’s American Jobs Plan will increase — not decrease — Democratic chances next fall.

For the moderate Democrats getting squeamish about taking on another big bill with a big price tag, remember that there are two factors that will dictate the difficulty of your race – the state of the economy and Joe Biden’s approval rating. Failing to pass the Biden Jobs Plan will undoubtedly mean a worse economy and a less popular president. Politics isn’t easy, but it isn’t that complicated either. Doing popular things is good politics – no matter what the conventional wisdom says.

Excellent column.

The Presidents we remember well are the ones who tried to do important things and did so with a sense of urgency. To win and motivate people you have to show what you stand for. The one and only way in which the Dems can win and retain new voters is to show that they understand, will fight for and will deliver on issues which make a difference in their lives.

In terms of Biden, in only a few months people who thought that he was just an insincere pol have been forced to confront the fact that he and his party are trying to do stuff. No acceptance of Republican attempts to define the agenda and no apology for being true to campaign promises. This is unequivocally good politics.

Making this a fight between "let's have a culture war" and "let's make people's lives better" is a fight worth having and, probably, the fight which will be easiest to win both next year and in 2024.

Our "inner Chomsky." That is hilarious and wonderful. If this is your writing on no sleep and new baby, well, I know you don't want this to be about you but about what you are saying, but your writing and thinking is really fantastic Dan. This was one of your best, the whole of it. How we need people like you. And each other here, for that matter. I really appreciate the readers who have become part of this group, too.